Poolhaus Blankenese, solo Exhibition in 2016

This exhibition was part of: Swing By 2, Poolhaus Blankenese Stiftung

Preis für junge Kunst 2016

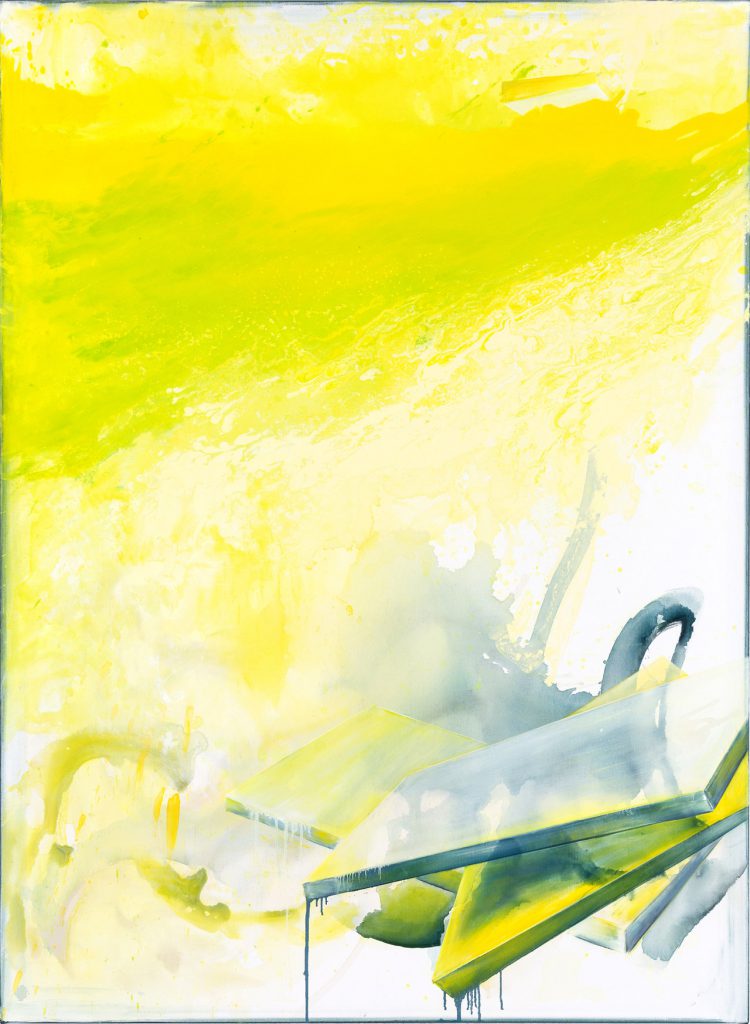

Acheron II, 2016, Tempera on canvas, 170 x 200 cm

Ludwig Seyfarth: Paintings in States of Matter

Art by Tanja Hehmann

There is flowing, steaming, spraying, splashing, running and congealing: what occurs in Tanja Hehmann’s paintings could perhaps be better described in states and processes than by tangible terms. Clearly, something is going on here, but not in the sense of a narrative act or story. If there is a “performer”, then it is the paint itself. Often arranged amorphously, it appears as matter, as a “self-referential” material. Simultaneously, the paint functions as a representation, whereby: anything that comes close to concrete objects nonetheless remains ambiguous. This pertains even to the geometric shapes reminding of architectural or crystal structures, which serve to provide some sort of linear framing to the otherwise irregular, seemingly unconstrained flow of colour in many of her pictures.

In her most recent paintings, such linear formations have receded in favour of the more flowing shapes. Here, the artist had first begun to work with generous planes of poured paint, without being able to fully predetermine its course. This further enhances the processual impression: what we see in the picture—despite its balanced composition—seems like a snapshot of an occurrence in a state of continual transformation.

The fact that a temporal element may be implicitly contained in a painting has been reflected upon already well before the invention of film and other motion picture media. One of the most well-known considerations of the theme is offered by the distinction between spatial and temporal arts in Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s essay “Laocoon” (1766): by condensing the process of a certain act into one “fruitful moment” in a painting (or a sculpture), even static media are able to “represent” time.

Around 1800, attempts were made to animate landscape pictures with the aid of sophisticated illumination techniques. Even Caspar David Friedrich was fascinated by the so-called “Mondscheintransparente” (moonlight transparencies), which by such methods offered the effect of a daylight view being transformed into a night view. But if Tanja Hehmann’s paintings recall works of the Romantic era, then it is less owing to the depicted subjects than a result of their tendency to dissolve into the ambiguous and processual. For when we focus more on the overall pictorial composition, rather than the representation, we will find that Friedrich’s and other Romanticists’ paintings feature central elements that we rediscover in modern and in contemporary painting, including Tanja Hehmann’s works:

the emptying of the pictorial plane, a stronger independence of colour and paint from the material quality of objects depicted, an increased emphasis of immaterial states compared to physically stable elements.

This phenomenon could also be described as the transition from the representation of solid materials to an enhanced sensitivity for “states of matter”. In physics, this term refers to the different aggregate states of matter caused by changes in temperature or pressure. In addition to the “classical” states of matter, solid, fluid and gaseous, solid matter is further distinguished as “crystalline” and “amorphous”. A crystalline solid is solid material arranged in a highly structured order, while amorphous solids display a certain plasticity.

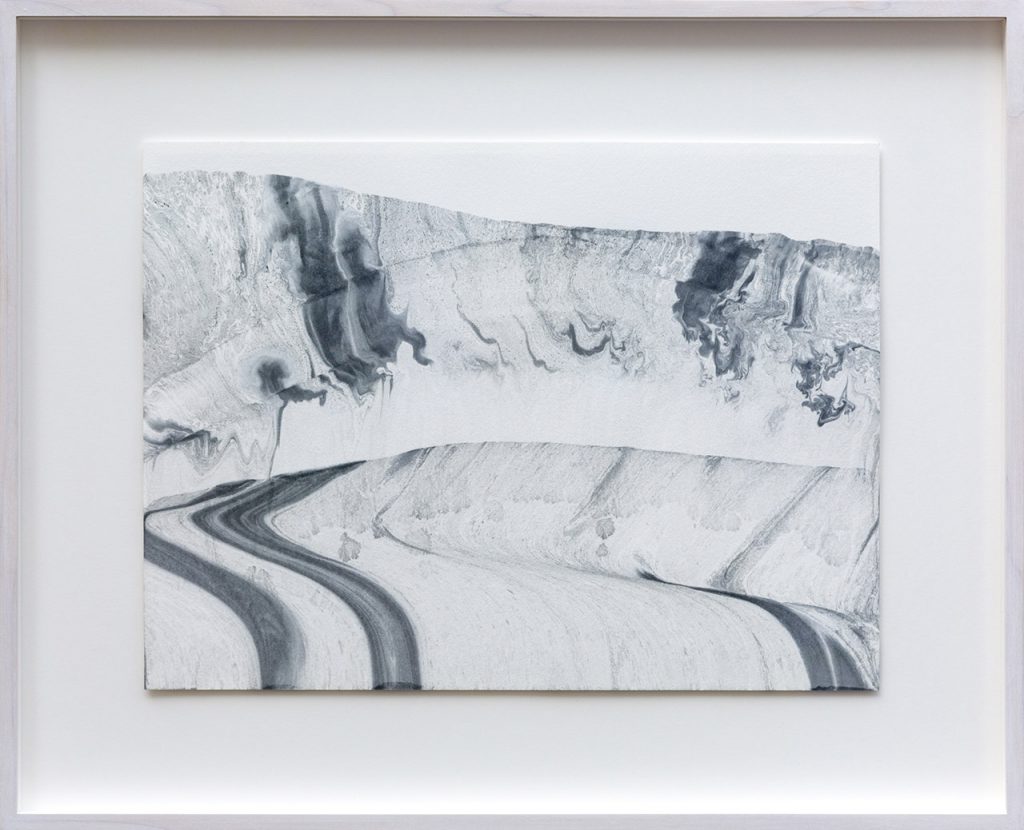

In her approach to painting, Tanja Hehmann explores—down to the most minute differentiation—the range of tension between the amorphous and the crystalline, between all that appears to be solid, fluid or gaseous. The same can be said of her works on paper, whose graphic structures unfailingly strike a balance between flowing and concrete elements. Here also, suggestions of material qualities are contrasted with the ambiguity of possible representational interpretations. The predominantly horizontally aligned structures could be read as landscape-like layering, but are equally reminiscent of microscopic cuts.

That the dimensional relations are just as ambivalent as the spatial references also applies to the large-format paintings. Only occasionally do they suggest that we enter into a pictorial space, as in Chiffre II, where rectangular shapes in the lower section of the picture are extremely narrowed down towards the back, as we know it from central-perspective images from the Italian Early Renaissance by Uccello or Mantegna.

This implied intense effect of depth is, however, immediately counteracted by an amorphous yellow colour field, extending itself over large parts of the picture plane, somewhat like a fog impeding visibility. So Chiffre II—much like all of Tanja Hehmann’s paintings—not only offers the eye much to see, but by merging material qualities and suggestions of spatiality in an almost paradoxical manner, it also addresses our tactile sense and entire physical being. Our senses are activated in order to seek orientation—a stability which ultimately is denied us.

Translated by Barbara Lang, German version below

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 150 x 110 cm

Ludwig Seyfarth: Eine Malerei der Aggregatzustände

Die Kunst von Tanja Hehmann

Es fließt, dampft, sprüht, spritzt, verläuft, gerinnt. Was sich auf den Bildern von Tanja Hehmann ereignet, lässt sich eher in Zuständen und Prozessen beschreiben als durch dinglich Greifbares. Es ereignet sich etwas, aber nicht im Sinne einer erzählerischen Handlung. Wenn es einen „Handlungsträger“ gibt, dann die Farbe selbst. In ihren oft amorphen Verläufen erscheint sie einerseits als Materie, als Material, das „sich selbst“ meint, aber gleichzeitig ist sie auch „Darstellung“. Alles, was an konkrete Gegenstände erinnern könnte, bleibt mehrdeutig. Das gilt auch für geometrische Gebilde, die an Architekturen oder an Kristallstrukturen erinnern, und die auf vielen ihrer Bilder den unregelmäßigen Farbverläufen so etwas wie eine lineare Rahmung verleihen.

Auf den neuesten Gemälden treten solche linearen Formationen jedoch hinter fließenden Formen weitgehend zurück. Hier arbeitet die Künstlerin auch erstmals mit großflächigen Farbschüttungen, deren Verlauf sie nicht vollständig voraussehen kann. Damit verstärkt sich der Eindruck des Prozesshaften. Was wir auf dem Bild sehen, erscheint – bei aller kompositorischer Ausgewogenheit – wie eine Momentaufnahme aus einem Geschehen, das in steter Veränderung begriffen ist.

Das auch in einem Gemälde implizit enthaltene Zeitmoment wurde schon lange vor der Erfindung des Films und anderer Bewegtbildmedien intensiv reflektiert. Eine der bekanntesten Erörterungen zum Thema ist die Unterscheidung in Raum- und Zeitkünste in Gotthold Ephraim Lessings Aufsatz „Laokoon“ (1766). Indem auf einem Bild (oder in einer Skulptur) der Ablauf einer Handlung in einem „fruchtbaren Augenblick“ gleichsam zusammengefasst wird, können auch statische Medien die Zeit „darstellen“.

Um 1800 versuchte man durch raffinierte Beleuchtungstechniken Landschaftsbilder zu animieren. Für so genannte „Mondscheintransparente“, bei denen sich eine Tag- in eine Nachtansicht verwandelte, begeisterte sich auch Caspar David Friedrich. Wenn Tanja Hehmanns Bilder an Werke der Romantik erinnern, dann weniger wegen der dargestellten Motive als durch deren tendenzielle Auflösung im Zweideutigen und Prozesshaften. Denn schauen wir statt auf die Darstellung mehr auf die Bildkomposition, finden sich bei Friedrich und anderen Romantikern zentrale Momente, die wir in der modernen und auch in der zeitgenössischen Malerei, so bei Tanja Hehmann, wiederfinden:

die Entleerung des Bildfeldes, die Verselbständigung der Farbe von der Materialqualität der abgebildeten Dinge, die zunehmende Betonung immaterieller Zustände gegenüber dem physikalisch Festgefügten.

Dies könnte man auch als eine Wendung von der Wiedergabe fester Materialien hin zu einer Sensiblisierung für „Aggregatzustände“ beschreiben. Physikalisch bezeichnet dieser Begriff die unterschiedlichen Zustände von Stoffen durch Veränderung von Temparatur oder Druck. Neben den „klassischen“ Aggregatzuständen fest, flüssig und gasfömig werden feste Stoffe in „kristallin“ und „amorph“ unterschieden. Kristallin ist ein fester Stoff, der seine Form nicht verändert, während amorphe Stoffe eine gewisse Formbarkeit aufweisen.

Tanja Hehmanns Malerei lotet das Spannungsfeld zwischen dem Amorphen und dem Kristallinen, zwischen dem fest, flüssig und gasförmig Erscheinenden bis in kleinste Differenzierungen aus. Das gilt auch für die Papierarbeiten, deren zeichnerische Strukturen stets eine Balance zwischen dem Fließenden und Festgefügten halten. Der Suggestion von Materialqualitäten steht auch hier die Vieldeutigkeit möglicher gegenständlicher Deutungen gegenüber. Die durch horizontale Gliederungen dominierten Strukturen könnten als landschaftliche Schichtungen gelesen werden, aber sie erinnern auch an mikroskopische Schnitte.

Dass Größenverhältnisse ebenso ambivalent sind wie die räumlichen Bezüge, gilt auch für die großformatigen Gemälde. Nur punktuell wird bisweilen suggeriert, dass wir einen Bildraum betreten könnten, wie auf Chiffre II, wo sich Quaderformen im unteren Bildfeld stark nach hinten verkürzen, wie man es aus den zentralperspektivischen Darstellungen der italienischen Frührenaissance bei Uccello oder Mantegna kennt.

Dieser angedeutete Tiefensog wird jedoch gleich wieder durch ein amorphes gelbes Falbfeld konterkariert, das wie ein die Fernsicht verhindernder Nebel einen Großteil der Bildfläche ausfüllt. Und so bietet Chiffre II – wie alle anderen Bilder Tanja Hehmanns – nicht nur dem Auge viel zu schauen an, sondern indem Materialqualitäten und Suggestionen von Räumlichkeit auf fast paradoxe Weise ineinander verschränkt sind, werden auch der Tastsinn und unser ganzes Körpergefühl aktiviert, um nach einer Orientierung zu suchen, die uns letztlich verweigert bleibt.

Oil on mould made watercolor paper

30 x 40 cm, 44 x 54 cm framed

Oil on mould made watercolor paper

30 x 40 cm, 44 x 54 cm framed

Entrance hall

Portico

Portico

Acrylic and oil on canvas, 150 x 110 cm

Oil on mould made watercolor paper

30 x 40 cm, 44 x 54 cm framed

Oil on mould made watercolor paper

30 x 40 cm, 44 x 54 cm framed

Oil on mould made watercolor paper

30 x 40 cm, 44 x 54 cm framed

Terminus II, 2016, Ink, acrylics and oil on canvas, 150 x 110 cm

Teahouse

All photos by Helge Mundt